Blade, The (1995)

[director Tsui Hark]

Color 104 min

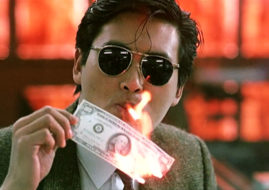

Director Tsui Hark is possibly the baddest-assed badass in the history of filmmaking and a wholly unique quantity in film history. In 1980 he almost single-handedly started the Hong Kong new wave with Warriors from the Magic Mountain. He revitalized and recreated himself many times within the next two decades, and, with his wife and co-conspirator Nansun Shi, he continues to make movies. His style is hyperkinetic, smashing beautiful, complex images together like so much flotsam to make, rather that a monument, a sort of magnificent shack, quickly built out of high-quality parts. Hark crams his movies with enough plot for two or three normal films, and his try-anything style often gives his movies a kind of free-flowing energy unique in filmdom. Sometimes it works, resulting in classics like Peking Opera Blues, sometimes it doesn’t, giving us messes like A Better Tomorrow III, and sometimes it just takes things plain over the top.

The Blade aims for “over the top” and never looks back. Hark’s previous films had sometimes been described as “120 minutes compressed into 90,” but this one is more like 180 minutes compressed into 120. The result is the most exhausting spectacle in the history of the movies, one of the most violent films ever, and what can be described as a kind of transcendent world-view. It is the most arresting film Tsui Hark has ever made, and one of the greatest three or four films of all time.

Everything about The Blade spits rage, from its mile-a-minute editing to its edgy, darting camera, to its furious performances and predominantly red-and-orange color scheme. Even scenes of dialogue that would normally be presented as calm are rendered here in violence. People enter rooms slamming doors open, they stride, leap, and often flip across the space between themselves and the other actors. The narrative is messy and deliberately overburdened with a ridiculously large amount of characters, especially villains. There are three completely different groups of bandits to keep track of in this film, as well as three protagonists and a small army of supporting characters related to each of the main characters.

Story-wise, it’s a variation on Chang Cheh’s old One-Armed Swordsman, a quintessential early martial arts film starring Jimmy Wang-Yu. The one-armed swordsman in this movie is On (easily the greatest performance of Zhao Wen-Zhuo’s life), who is adopted by a sword manufacturer after he is orphaned by a massively tattooed swordsman named Lung. On loses his arm and falls off a cliff defending Ling, the sword-maker’s daughter and narrator of the story, from a vicious bandit-attack. Ling tries to court On’s fancy, as well as that of On’s fellow factory-worker and friend, Iron Head. Ling and Iron Head run away together to look for On, who, having learned of his family’s unfortunate history from Ling, attempts to master a rather spectacular form of martial arts from half of an instruction booklet, using his father’s broken saber. On tries off-and-on to avenge his father’s death, but various life-circumstances get in his way, similar to the plot flow of Voltaire’s famous novel Candide. Along the journey, Tsui Hark manages to throw in a full range of supporting characters in order to illustrate Hark’s own concepts of loyalty, family, commerce, chivalry, and the eternal suffering of humanity, most especially women. Needless to say, it ain’t Disney. Hark has a view of the world that is as negative as it is rich in detail. Never before has such a fully-developed world-philosophy been laid to celluloid so quickly, comprehensively, and vividly.