Sydney Film Festival 2007

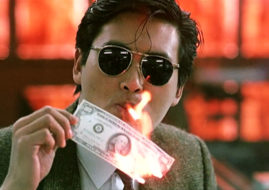

This week the Sydney Film Festival premiered a new Hong Kong film, Eye in the Sky, another cops and robbers movie that highlights the city’s steamy Blade Runner-esque backstreets.

[Australian News]

by Glenda Korporaal

This week the Sydney Film Festival premiered a new Hong Kong film, Eye in the Sky, another cops and robbers movie that highlights the city’s steamy Blade Runner-esque backstreets.

It’s not as good as Andy Lau’s Infernal Affairs, which was remade recently by US director Martin Scorsese into The Departed. But the tale of a young girl training to be a member of the police surveillance unit (the “eye in the sky”) would certainly lend itself to an astute Western remake. Introducing the film, the Hong Kong Government’s representative in Sydney, Jenny Wallis, argued that the three new Hong Kong-made films on view at the Sydney festival were another example of how the city’s lively filmmaking industry had continued to prosper under the “one country, two systems” arrangement with China.

Next weekend it will be 10 years since the rainy night when Prince Charles and the last British governor, Chris Patton, sailed out of Hong Kong harbour on the then royal yacht Britannia and the city was handed over to China or returned to the arms of the motherland, depending on your point of view. Despite all predictions of Chinese tanks rolling across the border on July 1, 1997, Beijing cracking down on civil liberties and Fortune magazine’s famous cover story flagging “The Death of Hong Kong”, the territory of seven million people has come through the ups and downs (or, more accurately, the downs and then ups) of the past decade pretty well.

There was a rocky first five years when Hong Kong was in a bit of a no man’s land, devoid of support from Britain (and the resources of Whitehall) while Beijing also kept its distance. The city was almost brought to its knees during the severe acute respiratory syndrome crisis of 2003. But the second five years has seen the city regain traction and re-emerge with a sense of energy and direction as a vibrant, active, but still very different part of China.

There hasn’t been a lot of progress towards democracy under Chinese rule (nor was there much thought about it until the last days of the British rule).

You could argue that China cut short the term of Hong Kong’s first Beijing-approved leader, Tung Chee-hwa, two years ago, following public protests against his leadership, making way for leading public servant Donald Tsang.

That Beijing has allowed a practising Catholic who was knighted by the British to lead Hong Kong also shows a lot of pragmatism. (During an interview in 2002 I asked Tsang, the then finance secretary, whether he would consider putting his hand up for the top job. The idea then was so radical, he told me abruptly that I had wasted my question.)

Despite Hong Kong’s freedom of speech, you don’t get senior politicians or prominent businesspeople launching into public criticism of China’s political leaders.

But as a sort of make-it-up-as-you-go political experiment, Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese sovereignty (it is run as a Special Administrative Region, as is Macau) has gone so smoothly that the political shift is largely ignored by the outside world as Hong Kong just gets on with business.

The stock market and the property market are booming as the city has reinvented itself as a modern gateway to China. Not just the gateway to the factories of southern China but also the international capital-raising centre of China as well as a tourist centre for increasingly wealthy mainland Chinese.

Shanghai is also growing rapidly as a domestic financial centre of China, with its shining Jetsons-like new buildings emerging from the Pudong skyline. But Hong Kong’s openness, its Western legal and business systems and internationalism, and the energetic, almost workaholic attitude of its people have helped it to defy predictions that it will be overtaken by Shanghai anytime soon.

The city is home to one of the finest Australian cinematographers, Chris Doyle (Rabbit-Proof Fence, The Quiet American), who can conduct almost simultaneous conversations in English, Mandarin and Cantonese while juggling a beer, a cigarette and a mobile phone.

Doyle works closely with one of Hong Kong’s most successful directors, Wong Kar-wai, whose post-1997 works include In the Mood for Love, My Blueberry Night and 2046. His followers are eagerly awaiting his latest production, The Lady from Shanghai.

Several celluloid swallows, of course, do not make a summer. Popular Hong Kong-made films largely do not take up big political issues that could cause problems in Beijing. But Brisbane-based Australian filmmaker James Lingwood, who lived in the city for 27 years, has just gone back there to complete his third documentary on Hong Kong, From the Mouth of the Dragon; he too finds a very up-beat city.

Based on a wide range of interviews from Hong Kong cultural types and leading expats such as Canadian-born property developer Allan Zeman, to the inevitable taxi drivers and workers in the wet markets, it shows a city on the move.

Lingwood’s documentary, which will be shown on BBC World five times next weekend (June 30, July 1 and 2), is the third in a series of Seven Up-style documentaries that he made in 1997, five years later in 2002 and now 10 years later in 2007.

“In 1997 people were concerned and worried about the political climate on a global scale,” he says. “People were worried about Hong Kong’s future with China. But 10 years on, nothing much has really changed.”

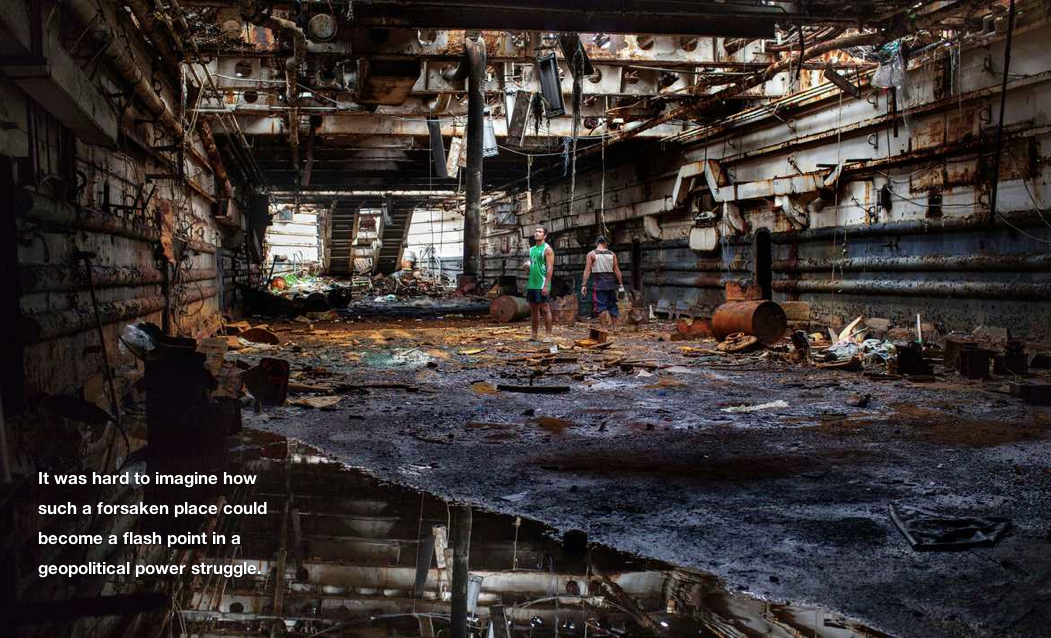

The reunification with China has seen the city reinvent itself, learning to capitalise on its new life with the roaring Chinese Dragon without getting burned.

Source: http://theaustralian.news.com.au

Related Posts

« Hong Kong Movies ‘Election’ Films Rise to the Top of the Hong Kong Gangster Class »